Ruby Angela Saleh wrote an emotional tribute for her deceased younger brother, Fahim Saleh, Gokada CEO. Read the tribute below:

In an article posted on Medium, she narrated how she found out about her brother’s gruesome murder.

‘On July 14th at 10:47 pm, my phone rang. I was in bed next to my husband and had just begun dozing off, but I answered because it was my aunt, calling from New York.

‘“I have some very bad news,” she said. She sounded spooked and was reluctant to divulge more, so I knew something really bad had happened to someone in my immediate family. My shoulders stiffened while the rest of my body went limp. Maybe one of my parents had Covid?

‘“What happened?“ I kept asking. “What happened?” I was having trouble drawing a breath. I put the phone on speaker so my husband could listen.

‘“It’s very bad,” she said.

‘Just tell me, Aunty. What happened?”

‘“Fahim isn’t with us anymore,” she said.’

Her first instinct was disbelief, she said.

She continued: ‘I dropped the phone and crawled onto the wooden floor, touching its cold, hard surface with the palms of my hands. I shook my head. “No, no,” I said, my hair falling over my face. “What are they saying?” I looked up at my husband. He was already crying, as if he had accepted these words about my brother as truth. His crying didn’t make sense to me because this news couldn’t possibly be real.

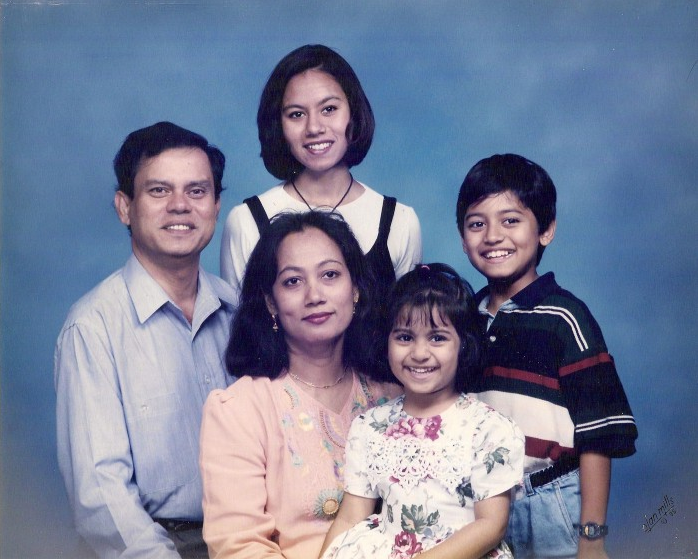

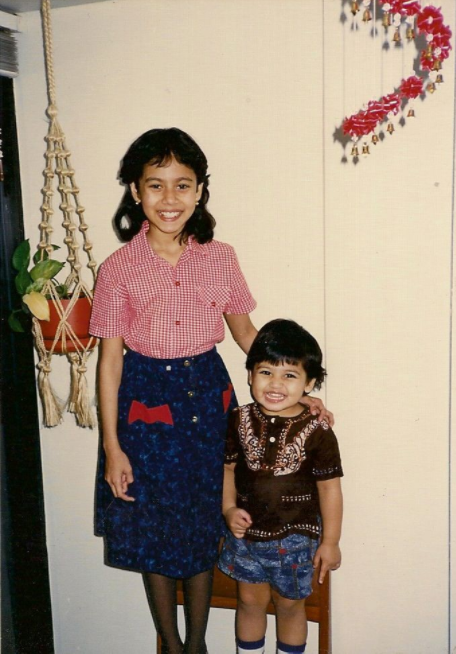

‘I flew across the Atlantic to New York the next day. Internet headlines about my brother’s murder proliferated. “CEO Found Dismembered In Manhattan Apartment,” one read. “NYC Cops Find Headless, Limbless Man Next To Electric Saw” another explained. This was MY baby brother they were talking about. MY Fahim, whom, when I was eight years old, my parents brought home from the hospital to me in an orange fleece blanket.’ She spoke about what it was like growing up with Fahim, how he started his first business at the age of 10 to support their father, built his first website at age 12 and monetised it such that he got his first paycheck from Google at age 13, a huge sum that surprised their father.

She wrote: ‘While we were growing up, I felt more like a mother to Fahim than a sister. When he was a toddler too wild to finish a meal, I ran after him with spoonfuls of rice and chicken. I gave him baths, I changed his diapers, and I was petrified the first time I saw his nose bleed. Something horrible is happening to him, I thought, watching blood gush onto his little yellow shirt. He was three then. I was eleven. Thirty years later, I was learning that Fahim’s head and limbs had been discarded in a trash bag. Someone had cut my brother’s body into pieces and tossed the pieces into a garbage bag, as if his life, his body, his existence had had no meaning or value. Messages began pouring in from friends. “I don’t know what to say,” most of them began.

‘“Oh, L, who would do this to my baby, my poor baby, my poor sweet brother?” I replied to one of my best friends. “This still feels like a nightmare I will wake up from…my poor sweet baby.”

‘We tried to protect our parents as much as we could in those first few days, but my sister and I spoke openly with each other. We had the same thoughts: Had he been scared? Had he begged for his life? Had he suffered? And if so, how much? We thought we wanted to know everything, but what we really wanted was to conclude that he hadn’t suffered or been scared, that he had gone quickly and peacefully. I wished I could hold him in my arms, caress his hair, and make everything okay.’

She spoke about the first time she saw her brother’s dismembered body and how she reacted to it.

She wrote: ‘Within 48 hours of hearing the news, I was sitting with my cousin and sister on floral bedsheets on my cousin’s cast iron bed when I got a call from the funeral home. The man on the line said that due to Covid, I would have to identify my brother’s body via a photo he would send to me. His message popped up within minutes. I immediately felt nauseated. “It’s here,” I said. My sister, cousin, and I held hands and said a prayer before opening the attachment. And there it was: a photo of my beautiful brother, lifeless.

‘My sister howled. “No, no, no, it’s real now, it’s real now,” she kept repeating.

‘I held her tight. We wanted to ask that photo, ask our beloved brother, “How did this happen to you, baby?” I began to caress his face on the computer screen with my index finger as tears poured down my cheeks. I just wanted to tell him, “I’m so sorry, Fahim, I’m so sorry, Fahim. My poor, sweet brother. My heart.” ‘

Speaking of the day of his funeral, she wrote: ‘On Sunday, July 19th, 2020, my family and I had to bury my sweet brother in the Hudson Valley. I had to arrange my beautiful boy’s funeral.

‘Three days prior, the funeral home called to report that it would not be possible to sew his limbs and head back onto his torso before burial. Upon receiving that news, I closed my eyes and crossed my arms over my chest like a Pharaoh, squeezing my phone against my body. My hands formed fists that I pushed into my heart with all my strength to contain my pain.

‘Then I pleaded with the man to make sure all of my sweet brother’s body parts were in their proper places in the casket. The day before the funeral, the man called me again. “It wasn’t easy, but we were able to put him back together,” he said.

‘The morning of the funeral, I laid restless and limp in my sister’s bed at 3 a.m. listening to my parents sob together in Fahim’s room, with the checkered bed sheets and our childhood photos on the wall, their conversation too muffled behind the wall to understand.

‘My family and I looked at our sweet boy’s face in the casket. He seemed to be sleeping peacefully. His body was covered in a white sheet, ice packs placed on his torso, his beautiful eyelashes long and lustrous against his skin. His hair was matted down, not spiked like usual, its blond tips glistening under the hot sun. Our father approached the casket and began to speak to Fahim in the affectionate voice with which he often addressed him. “Fahim Saleh, didn’t I tell you not to dye your hair? Didn’t I tell you?” he said before he began to sob. Our mother kept repeating, “Ok, you sleep now, baby boy. You get some rest. You sleep now.”

‘As the cemetery workers lowered my brother’s casket into the ground, my father stood at the head of the grave and shouted, “Fahim, don’t go. Fahim, don’t go. Fahim, Fahim, Fahim, Fahim….” ‘

She continued: ‘Exactly one month ago, my brother returned from a three-mile run and was murdered in his apartment. Sometimes it still doesn’t feel real that Fahim is gone. And sometimes it feels too precisely like the cruel, heinous, and unbearable reality that it is, letting me see nothing but darkness and feel nothing but piercing pain in every quadrant of my heart. As I reminisce about Fahim, I know that he was the most special gift given to us, and then taken away. Now, our father spends his days sitting next to Fahim’s dog, Laila, speaking to her in the same affectionate tone he reserved for my brother, watching videos of or reading about the accomplishments of his deceased son. My mother spends her days crying. At night, she cannot sleep.’

See few pictures below:

![#BBNaija: Prince In Tears As He Sends Emotional Message To His Elder Brother [VIDEO] #BBNaija: Prince In Tears As He Sends Emotional Message To His Elder Brother [VIDEO]](https://talkglitz.media/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Fotoram.io-15-1-150x150.jpg)